"Pianola" as a collective term for self-playing upright and grand pianos hardly suggests the great variety of these instruments. This diversity is due to the successive development of technical possibilities and the different demands of the buyers - but also to the large number of manufacturers who wanted to participate in this lucrative market. Many of these manufacturers tried to push through their own ideas - or to circumvent existing patents and therefore built new variations of the pianolas which were similar in basic principle.

The following characteristics can be used to distinguish between the various Pianola systems:

Construction (cabinet, front, upright piano or grand piano)

Construction (pedal piano, art pianoforte, reproduction piano)

Scale (number of notes addressed on the note sliding block) and

Basically there are four different designs: The cabinet, the push-up player, the upright piano, the upright grand piano.

THE CABINET

Cabinet is the name given to those systems that combined the self-playing technique with an acoustic piano in one cabinet, but did not have their own keyboard. The acoustic piano in the cabinet was purchased from leading manufacturers, mostly from Feurich. With these systems, the self-playing technique directly accesses the mechanics of the piano. As far as we know, these are exclusively reproduction systems that play the music fully automatically and with emphasis. These systems are especially suitable for music lovers who only want to hear the music from the rolls of music and do not play the instrument themselves. Cabinets were built by Welte, Philipps and Hupfeld - today they are rarely found - and, if at all, mostly by Welte-Mignon.

THE COUNCILOR

The so-called push up players were the first systems to be produced in large numbers. Pianola of the Aeolian Company and Phonola of the Hupfeld AG are well-known examples. A push-up player is pushed in front of a manual piano or grand piano. The self-playing technique is located completely in the Vorsetzer. The Vorsetzer usually has 65-88 fingers (other/formerly also less), which are placed on the keys and thus play the music read from the music roll directly over the keyboard. The Vorsetzer was available in all three designs, as a pedal instrument (early pianola/phonola etc.), as an art playing instrument (later pianola/phonola etc. with accentuation possibilities) and as a reproduction instrument (Welte, Hupfeld DEA, etc.). Vorsetzers are interesting if you want to enjoy the sound of an already existing upright or grand piano - or if you want to use different instruments with the Vorsetzer.

THE PIANOLA INSTALLATION PIANO

Soon the manufacturers of self-playing mechanisms realized that more and more customers found it cumbersome to set up the presetters in each case, since they not only had to be pushed close to the instrument, but also had to be correctly adjusted in height, pedal position and playing strength. In addition, fewer and fewer people wanted the additional furniture in their homes. Last but not least, lucrative additional business opened up for the manufacturers of the self-playing mechanisms through the sale of combined instruments. So it did not take long for manufacturers such as Aeolian or Hupfeld to cooperate with many well-known manufacturers of upright and grand pianos - or to take them over later on - and offer upright pianos in particular.

THE PIANOLA INSTALLATION GRAND PIANO

From 1908 onwards, the pianola systems were increasingly installed in upright and grand pianos. With the pianola technology built into the instrument, the instrument could be used as a hand playing instrument and as a pianola. With upright pianos, it soon became apparent that many customers found the boxes for accommodating the pedals on the grand piano optically too bulky and that the operation of the often shortened normal piano pedals was not so convenient. With later electrically operated Pianola grand pianos, these were then no longer necessary as the suction air supply was provided by the motor.

In addition to these main construction forms, there were also a large number of other creative self-play solutions, but these did not catch on. There were substructure apparatuses for grand pianos, keyboard attachments for upright pianos, etc..

TYPES OF THE PIANOLAS

Three main types can be distinguished

the pedal mechanism

the art play instrument

the reproductive instrument

All three types were available in the four designs mentioned above - and in combinations of the types in one instrument (e.g. Hupfeld Tri-Phonola). Exceptions are the so-called cabinets, as these were mostly designed as reproduction instruments. The pure pedal instruments became rarer from about 1907 and were replaced by the so-called art instruments. The construction types differ in the way they reproduce different rolls of music.

THE PEDAL INSTRUMENT

As a construction it is the simplest and early form of the standard pianola. The self-playing mechanism for playing the music rolls is driven by pedal operation. The music roll contains only the punchings for the notes taken from the sheet of music, no punchings for emphasis, tempo, dynamics. The task of giving the piece of music emphasis and expression falls to the so-called pianist, i.e. the person sitting at the pianola. In one of his instructions, Hupfeld wrote concrete details about the operation of the levers (see picture opposite).

With this type of pedal piano construction, "self-playing" instrument is only partly the right term. Although the notes are played in the correct order and composition via the music roll, it is up to the pianist to make a melodious and, if necessary, beautifully interpreted piece of music out of it, since the pianist controls tempo, dynamics and intonation. Many scrolls have information on them, so that the pianist can control the dynamics and intonation of the music as it is intended for this piece of music by the scroll manufacturer. In fact, the pedalling technique is crucial to the creation of music with this type of pianola.

Very soon the demand for these pedal instruments increased and customers wanted a less mechanical and often lifeless sounding musical experience. So around 1907 so-called artist rolls came onto the market - here the notes of a piece of music are placed on the music roll in the same way as a particular pianist played this piece - so the first "recordings" were made. In most cases, the pedal (right pedal) and the melody accentuation were already provided for on the scroll and placed through perforations. Until the standardization this was done in a manufacturer-specific way. However, the pianist was still responsible for shaping the dynamics and intonation, so that he could either follow the dynamic and intonation commands on the roll in the sense of the recording pianist - or make his own interpretation. In order to be able to play these artist roles, artistic playing instruments were brought onto the market.

THE ARTISTIC PLAYING INSTRUMENT

By extending its functions, the pedal instrument became an art playing instrument. Additional functions are: automatic melody accentuation (soloist for Hupfeld, themodist for Aeolian, melodant for Angelus, etc.), pedal function (fortepedal=right pedal), which are also automatically controlled by corresponding perforations on the note rolls. In addition to the levers of the pedal piano, further levers for switching the melody accentuation and pedal function on and off are thus usually found in the area of the music roll box.

From about 1908 on, artistic playing instruments were the dominant type of pianolas. Depending on the manufacturer, the quality of equipment and workmanship varied. In Germany Hupfeld dominated this market. At the beginning, art pianos were mainly available with pedal pedal function - later, however, they were also available with an electric blower system, which then had automatic switch-off, rewind, partial repeat function and sometimes simple emphasis functions.

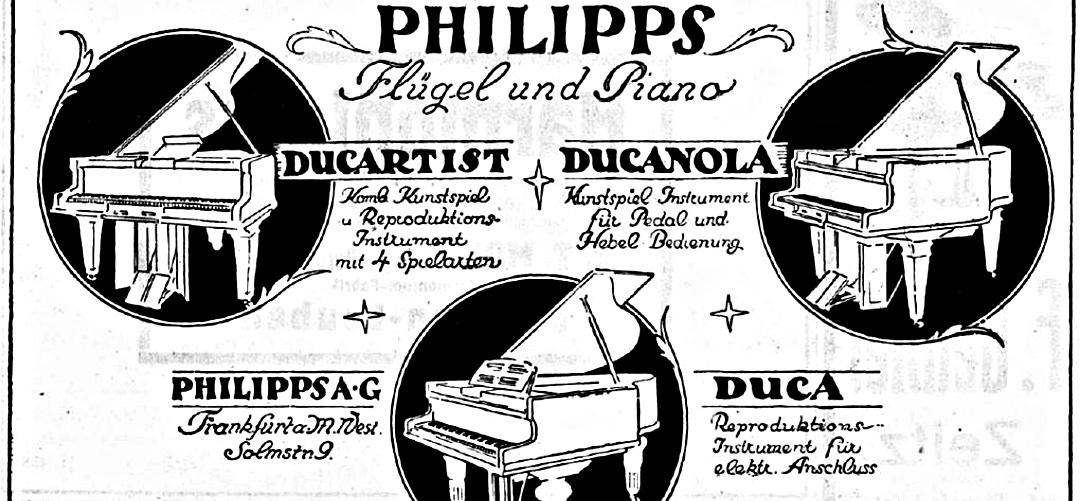

Examples of manufacturer-specific names of the art playing instruments are Solophonola by Hupfeld, Pianola Themodist by Aeolian, Ducanola by Philipps, Estrella by Popper, etc.

THE REPRODUCTIVE INSTRUMENT

It was already introduced in 1904 as "Artist" by Hugo Popper from Leipzig and M. Welte und Söhne from Freiburg. Mr. Welte and Mr. Bockisch were interested in recording a pianist's playing with all its details and reproducing it using a suitable device. Quoted from a Welte company brochure, it says: "Even the most carefully drawn mechanical music will always sound mechanical, it lacks the freedom of movement, the natural flow, the momentum of perception, the often inconspicuous yet so charming changes of tempo. In short, the playing does not have what makes it "artistic", what makes it "perfect". After a long period of study we realized that the only solution that thoroughly eliminates all the aforementioned imperfections is to be found in the recording of the pianist himself and its reproduction on a grand or upright piano. “

The special music rolls for reproduction instruments contain all the information required for fully automatic playback of the piece of music. The pianist is neither able nor intended to influence the reproduction as in the case of the upright piano. The realization of the high quality of reproduction has been achieved in different ways by the manufacturers. This also means that reproduction music rolls only work on the instruments of the respective manufacturers and develop the intended quality. The reproduction instruments play 80-88 notes and have an additional 10-25 holes in the note sliding block for the control. You will find more details about the instruments and the music rolls on these pages in the respective categories. Especially interesting are of course those scrolls which are the only sound documents - like Alfred Reisenauer, and many others.

MAIN REPRODUCTIVE INSTRUMENTS

Welte-Mignon red (T100) from 1904

Hupfeld DEA (from 1907)

Philipps Duca (from 1908)

Aeolian DuoArt (from 1913)

Ampico A from 1913

Hupfeld Triphonola (from 1919)

Welte-Mignon green (T98) from 1924

Ampico B from 1929

In addition, there were other reproduction instruments, which, however - like the Popper Stella from 1908 - never achieved a significant market share and for which there are almost no reproduction rolls today.

The Ampico B can be regarded as the last development stage of these reproduction instruments. In the book "Re-Enacting the Artist" Larry Givens writes about the Ampico B system: "With its fewer moving parts, its electric roll drive mechanism, its quieter pump and exhaust, its rapid-acting valves, and many other improvements and innovations the Model B Ampico cannot be considered anything less than the zenith of player piano development. „

All reproductive instruments were equipped with an electric blower - integrated into the instruments, as an adjacent blower in a cabinet or chest, and as a central supply in a separate room. Reproduction systems were available as presets, keyboard-less cabinets and built into upright and grand pianos. Some reproduction systems could also be used additionally as art pianos. This is indicated, for example, by the designation "Duo" in DuoArt or "Tri" in Triphonola, i.e., for the Triphonola, the three different possible uses in one instrument.

Of course, there were still many designs in which a piano was operated as a self-playing instrument alongside others - these so-called orchestrions will not be discussed in detail here.

SCALE OF A PIANOLA

The scale of a pianola indicates the structure and range of the tone and control spectrum available on the note slide block via holes. Most pianos up to ~1945 had 85 keys, on many grand pianos and so-called concert pianos often 88 keys. In the beginning only a part of the tones available on the piano were addressed by the pianolas.

Among the most important and common standard scales for pianolas are the

65 scale (Aeolian, from ~1897)

72/73 scale (horn field, from ~1902)

88 scale (standard, from ~1908)

This aspect of the larger tonal range for the reproduction of musical pieces in the original notation was highlighted by the companies as an important differentiating feature. In the case of reproduction instruments, differentiation was also attempted with the range (e.g. Philipps Duca with exactly one tone more than Welte), and, each manufacturer had its own patents for the control of the intonation apparatus, so that different scales were also introduced here and retained for a long time. It was not until the 1920s that Welte and Hupfeld, for example, offered their reproduction instruments with a scale that corresponded at least in terms of the size of the music roll to the standard 88 scale. This meant that standard 88 scale music rolls could be played (then only as an art play function).

A much-cited analysis by Chase & Baker from 1908 based on the 3838 rolls of music in their catalogue showed that with the scale of 65 notes, significantly fewer pieces of music could be converted 1:1 from sheet music to rolls. Of the 3838 music rolls, 1130 (29%) could be played with the 65 scale. 2425 (63%) rolls of music needed a scale of 78 tones, 2542 (66%) needed 80 tones, 2660 (69%) needed 83 tones, 3676 (96%) needed 85 tones and all rolls could of course be played with the scale of 88 tones. In order to be able to reproduce pieces of music on the 65 scale, reductions and octave shifts were made to stay within the 65 tones. This Chase & Baker analysis influenced the decision for a 65 standard and an 88 standard scale. Although this standardization was determined in America and only by the leading American companies, the European manufacturers also gradually followed the 88 standard, which was considered modern.

BUILDING STYLES OF THE PIANOLAS

Of course, the various manufacturers have tried to build their instruments in such a way that they were able to achieve more sales than their competitors on the market. This can be seen both in the design of the self-playing equipment and the design of the corps of the pianolas. The style design was adapted to the different groups of buyers, markets and contemporary tastes. Instruments for private households were designed differently than instruments for use in cafés or restaurants. The technical implementation of the self-playing mechanisms - although similar in basic principle - differs from manufacturer to manufacturer, and often there is no uniformity between the different systems, even within one manufacturer. Reproduction instruments were often housed in exceptionally artistically splendid cases, partly based on artist's designs and individually designed according to the buyer's furnishing style.